When Nicholas came out as bisexual to his classmates in the ninth grade, most of them were receptive. One of his friends, however, was “taken aback.”

His friend told him, “you know, I don’t usually hang out with f******s, but I guess I can make an exception for you.”

Nicholas, who grew up and attended public school in Macon, said the bullying he experienced didn’t end with comments.

“You get stopped invited to go over to people's houses, you know, certain friends don't want to hang out with you. And it's just little things like that you really don't realize as a kid, but more as an adult you realize, oh, this happened because I came out of the closet,” he said.

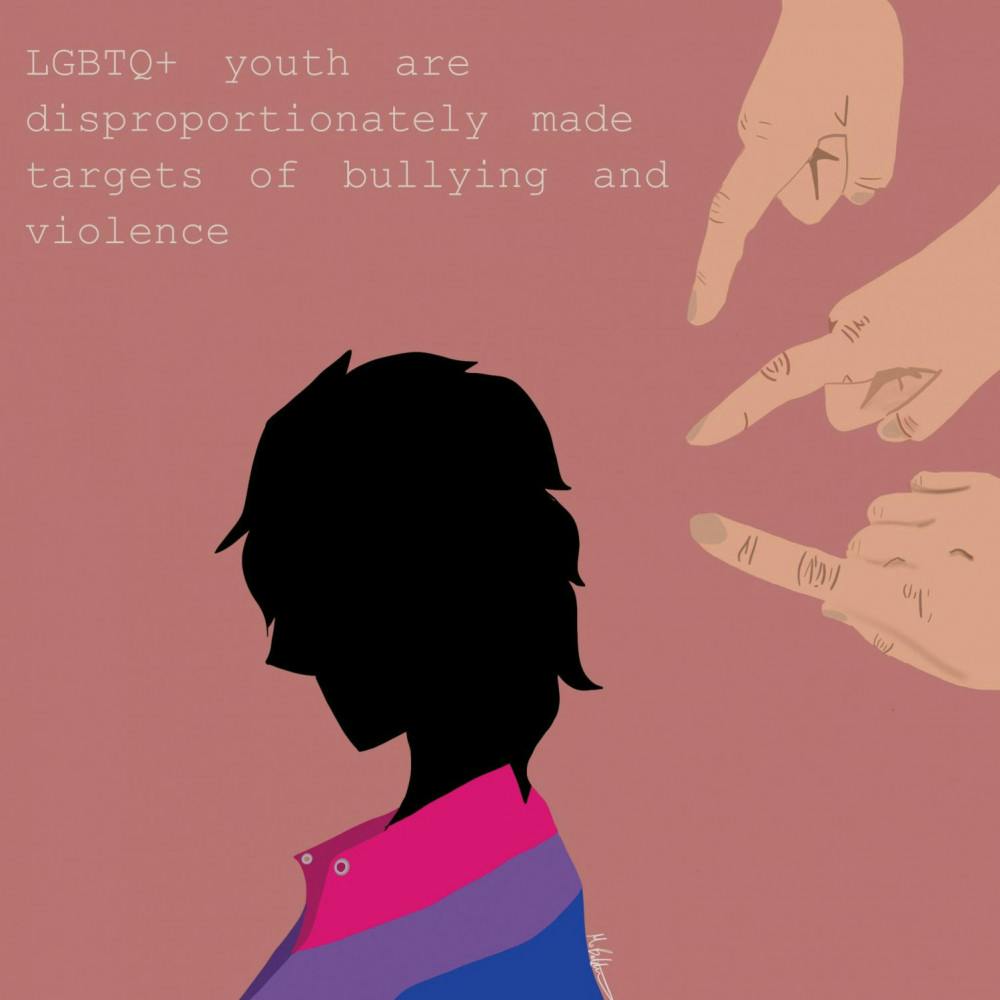

LGBTQ+ youth are disproportionately made targets of bullying and violence

Nationally, youth who are or are perceived to be part of the LGBTQ+ community are disproportionately made targets of bullying and violence at the hands of not only their peers, but also at the hands of adults such as teachers, family members and friends’ parents.

The 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance report conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that students who identify on the LGBTQ+ spectrum are at increased risk for bullying. While 17.1% of heterosexual students nationally reported being bullied on school property and 13.3% reported cyberbullying, 33% of LGBTQ+ students were bullied at school and 27.1% were bullied online.

The Georgia Department of Education collects yearly data on the prevalence of bullying in public schools by county. The data doesn't specify how many cases involve LGBTQ+ youth. However, Bibb County Schools reported 232 total cases in the 2017-2018 school year and 278 cases in 2018-2019.

The effects of bullying prompt academic, personal and emotional problems. Ten percent of LGBTQ+ students reported being so worried about their safety that they skipped school, according to Stop Bullying, a federal resource. The organization found that “bullying puts youth at increased risk for depression, suicidal ideation, misuse of drugs and alcohol, risky sexual behavior and can affect academics as well,” and LGBTQ+ youth are at increased risk for all of these.

‘Being in a fraternity I think is where I received most of my discrimination for being bisexual’

[sidebar title=align="left" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]

Nicholas did not want to share his last name due to the sensitive nature of his story.

[/sidebar]

Nicholas, now a third-year at Mercer University, said the bullying didn’t stop when he began college. He joined a fraternity his freshman year, and between the gendered environment of fraternity life and the lack of resources available for LGBTQ+ youth, he often felt isolated.

“Being out and being in a fraternity was, I think is, significantly harder than being straight in a fraternity, because the fraternity I was in often gave the perception of us like we are, you know, this masculine-type organization,” he said. “The idea of bringing men back to the fraternity house never crossed my mind, and I never did it for the fact that you’d get made fun of for it.”

Nicholas said he felt pressured by the hypermasculinity emphasized within the fraternity to downplay his sexuality.

“Being in a fraternity I think is where I received most of my discrimination for being bisexual,” he said. “I really haven't dipped into the more homosexuality side of, you know, who I am, or I've kept it more hidden because you have to get this manly persona.”

He said that since leaving the fraternity, he’s been more open to exploring his attraction to other men. On a trip to Madrid over the summer, he went to his first gay bar.

Compared to the southeastern United States, he said “the LGBT community is highly supported” in Spain. He’s also spent time in California, where he said the more socially liberal environment provides a welcoming space for LGBTQ+ people.

‘The assumption was that gay people did not exist in our community’

Gabby Koyfman is a student at Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, 40 minutes from her hometown of Suwanee. Like Nicholas, Koyfman also identifies as bisexual.

She said she knew that she was attracted to women as early as middle school, but didn’t feel comfortable coming out until her first year of college. The culture in her high school was one reason she didn’t disclose her identity for so long.

“From the outside, it looked like a very accepting school, but once you were actually there, you felt so ostracized,” she said. “It definitely made me feel a bit afraid later on to come out, even to the people that were gay, even though it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to be afraid of that. But later on, just experiencing the kind of Christian and conservative community that I was in, it just made me feel nervous that people were gonna think differently of me, that I was gonna be a different person if I took that step.”

She said that LGBTQ+ issues and identities were rarely discussed in the classroom, but when they were, it created a culture of erasure.

“The assumption was that gay people did not exist in our community, and that whenever we did talk about gay people in class, it was people that were ‘over there.’ You know, they exist somewhere, but they’re not here,” she said. “The way that the bullying took form was the assumption that they did not exist in the classroom, or if they did, it was something to be shocked about.”

She said she didn’t feel comfortable going to faculty for help, in part because many of her teachers were the ones enforcing the idea of LGBTQ+ youth as “other” in the classroom.

Her friends, most of whom also identify on the LGBTQ+ spectrum, were supportive when she came out, but Koyfman said her parents weren’t sure how to react at first.

“My mom still kind of has this idea that women that are attracted to women are masculine, so her thing was more like, ‘I think that you’re confused. I don’t think that you’re actually attracted to women.’ Which, we’ve grown past that now, but in the moment, that was her reaction,” she said.

[pullquote speaker="Gabby Koyfman" photo="" align="right" background="off" border="none" shadow="off"]The way that the bullying took form was the assumption that they did not exist in the classroom, or if they did, it was something to be shocked about.[/pullquote]

Koyfman’s concerns about coming out reflect a national culture of discrimination against bisexuals, known as biphobia. The Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy at the University of California- Los Angeles found that over half of non-heterosexual Americans identify as bisexual. However, only 28% of bisexuals said most or all of the important people in their lives knew about their sexual orientation, compared to 71% of lesbians and 77% of gay men, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

The reluctance to come out often stems from fear of rejection. The Pew Research Center study found that 30% of bisexuals were subjected to slurs or jokes, while 31% were rejected by a friend or family member due to their sexuality. Nearly half of LGBT adults feel that there is “little or no social acceptance” for bisexual men in particular, the study found.

For Koyfman and Nicholas, much of the biphobia they’ve experienced came from within the LGBTQ+ community. When Nicholas visited his first gay bar in Madrid, some of the friends he went with diminished his bisexuality.

“I experienced, you know, multiple things, but my gay friends over there, they’d be like, ‘you're not straight. You're not bi, man, you're just gay,’” he said. “That really puts you down. But you really have to reassert yourself.”

Nicholas attributes some of that biphobia to the way bisexuals are portrayed in entertainment media. Often, because bisexuals are attracted to more than one gender, they are assigned the stereotype of being indecisive or more likely to cheat on their partners.

The Los Angeles Times reported that many bisexuals “avoided coming out because they didn't want to deal with misconceptions that bisexuals were indecisive or incapable of monogamy — stereotypes that exist among straights, gays and lesbians alike.”

Koyfman said another aspect of biphobia is the idea within the LGBTQ+ community that bisexuals in “straight-passing” relationships cannot attend LGBTQ+ Pride events, should not bring their partner to these events or are not considered marginalized.

“That still doesn’t make you straight. You’re bisexual, and I still think you should be able to celebrate that if you want to,” Koyfman said.

Attitudes towards LGBTQ+ Americans are changing both on and off campus

While the LGBTQ+ population as a whole still grapples with discrimination in the United States, attitudes continue to shift towards acceptance.

In 2004, the Pew Research Center found that 60% of Americans opposed same-sex marriage while just 31% favored it. By 2019, the numbers had flipped: 61% of Americans supported it outright while 31% opposed.

LGBTQ+ Americans report that they have felt society become more welcoming to them. In 2013, an overwhelming majority of 92% of LGBTQ+ Americans said they felt more accepted over the past decade.

[pullquote speaker="Kyle Shook, Mercer alum" photo="" align="left" background="off" border="none" shadow="off"]I don’t know that the university realizes the very real fear that queer kids at Mercer face.[/pullquote]

Mercer University’s relationship with the LGBTQ+ student body has also evolved. In 2006, the Georgia Baptist Convention ended its 170-year financial partnership with the school over concerns that Mercer “is more liberal than its Southern Baptist roots,” due in part to Mercer’s decision to support a National Coming Out Day event on campus hosted by the Triangle Symposium, the gay-straight alliance which became Common Ground. The Cluster also played a role in the split, according to the Baptist Press, as 29 faculty and staff took out an advertisement in the newspaper to endorse the event.

Since the split, LGBTQ+ students are increasing visibility on Mercer’s campus. Common Ground runs a Facebook group with more than 360 members and a website which maintains a map of gender-neutral restrooms on campus. Members host weekly meetings and manage events such as the annual drag show. The group was allowed to host the show on campus for the first time in 2019, according to previous reporting by The Cluster.

However, challenges remain. Mercer administration made the decision in 2018 to invite Jay Sekulow, a lawyer on President Donald Trump’s legal team, to campus as that year’s Founders’ Day speaker. Students and alumni signed a petition asking that his invitation be canceled due to his history of arguing against same-sex marriage and supporting anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiments as the chief counsel of the conservative American Center for Law and Justice.

According to national progressive media who covered the fallout from Founders’ Day, students and faculty protested Sekulow’s speech by skipping the event, attending in LGBTQ+ pride attire or “grilling” him on his stances at a question-and-answer session that followed the speech.

“I don’t know that the university realizes the very real fear that queer kids at Mercer face,” said Mercer alum and former Common Ground officer Kyle Shook. “There is a lot of progress yet to be made for LGBT students.”

Those students have continued to advocate for a more welcoming campus since Sekulow’s speech. In 2019, McPherson Newell and Cefari Langford developed the Rainbow Connection training course, a voluntary initiative to help faculty at Mercer become more sensitive towards and respectful of LGBTQ+ students and the challenges they face on campus, and in 2017, Mercer alum and former Common Ground President James Stair conducted formal research and activism advocating for gender-inclusive housing options on campus. Current students have undertaken the project since Stair graduated.

Common Ground continues to meet Tuesdays from 6-7 p.m. in Knight Hall room 100.

*Nicholas did not want to share his last name due to the sensitive nature of his story.